The written language is powerful. Imagine: with the spoken word, we can talk from person to person, but the words, once spoken, must be heard immediately by someone nearby or are lost to the winds forever (barring telephony, repetition, and echoes). With the written word, however, we can leave words in a physical medium, transmitting them across time and space to people we may never know or see. The ancients understood this; Thoth, the god of writing, gave men a power of the gods when he gave the Egyptians hieroglyphs, and the Jews have kept their scriptures written since Moses first had them inscribed on Mount Sinai. Writing is something from the gods, and we usually take it for granted.

Occultists in the Western tradition, derived from Hermetic principles, never quite lost that reverence for the written word. They also held writing as something magical in its own right, which led to the tradition of grimoires and spellbooks that had power in and of themselves. We have sigils derived from angels’ names, we have writing systems derived from the stars themselves, and we use them to communicate to entities that go so far beyond our comprehension that it’s a miracle we can communicate with them at all. Of course, the writing systems that the occultists of yore used had another purpose: keeping the occult occult. Magic was never universally welcomed, and was sometimes persecuted and burned wherever orthodox zealots could find it cropping up. Special writing systems used to keep certain texts private or secret served their purpose, too.

Although the Roman and Hebrew scripts, and occasionally the Greek script, suffice for many occult tasks and practices, sometimes a certain task calls for a different kind of writing, either to cloak the intent or purpose of a certain text or to have spirits of any rank understand it easier for them. Below is a selection of writing systems I find myself using from time to time.

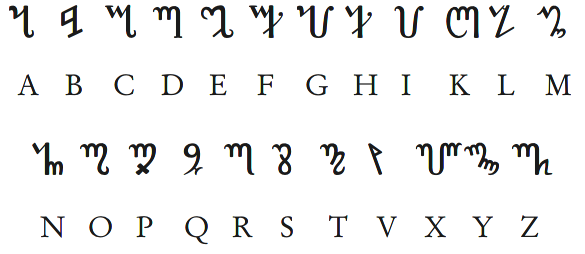

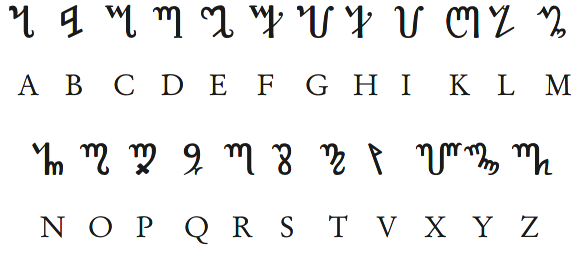

The Theban Script

The Theban script is a magical script, still in use in some Wiccan circles today. Both Johannes Trithemius and Cornelius Agrippa give versions of the Theban script, which was supposedly developed by the mage Honorius of Thebes to write his “Sworn Book of Honorius” in. Given the one-to-one correspondence with the Roman alphabet in use at the time (I and J were considered the same letter, as were U, V and W), the Theban script was likely developed as a cipher for the Roman script for alchemical texts in medieval Europe. It is used to cipher texts written in languages written with the Roman alphabet, such as Latin, French, or English. Although I tend to use the Roman script instead of the Theban when writing occult texts, I’ll switch to Theban when I require secrecy or protection from prying eyes.

The Celestial Script

The Celestial or Angelic script was used by Agrippa to write the names of angels and other celestial beings. Agrippa based this off the Hebrew script, with which it shares a one-to-one correlation (save for the final forms of the letters kaph, mem, nun, peh, and tzaddi, which aren’t present in this script). However, since Agrippa intended to use this script to communicate with angels and other celestial beings, he used forms of the letters that he derived from constellations in the sky, hence the angular nature of the letters with the little “star points”. The Celestial script shares some similarities with two other scripts Agrippa derived, Malachim and Passage du Flueve, which also share “star points” but the letterforms are much different. I prefer this script when inscribing or writing anything dealing with supralunar entities or planetary tasks. For information about Celestial and Hebrew, check out the post Celestial versus Hebrew.

The Alphabet of the Magi

The Alphabet of the Magi is another magical script used for Hebrew texts. It was developed by Paracelsus, an alchemist and magician in the 16th century, for inscribing on talismans and other magical objects. It, like the Celestial script, is based on a cipher of Hebrew, and might be thought of as a Hebrew parallel to what the Theban script is to the Roman script. I haven’t seen it used in any but a few astrological talismans, so it’s one of the more uncommon scripts, but it’s definitely a different kind of script than Celestial and might be suited for different purposes. Although I prefer the Hebrew script to deal with mundane magical things as opposed to the Alphabet of the Magi, this is still a useful script.